Post-ACL notes on the interpretability of sparse word representations

Participating at ACL2017 gave me the opportunity to get involved in lots of inspiring discussions. Here, I would like to leave a short note on one of the topics which arose during (and after) the conference multiple times related to the work I presented, namely the human interpretability of sparse coded word representations. I would like to particularly thank Abi See for her insightful questions so far.

As discussed in an earlier post, the work I presented at ACL was on employing sparse word representations for sequence classification. In my talk I argued that the popular dense word representations have a rather unintuitive behavior, namely, that they always try to take a stand on every single aspect of every single word. Assuming that some dimension in a distributed (dense) word representation roughly corresponds to some concept (e.g. the cuteness of the given thing), we would expect to see high values along that dimension for words describing things that are generally regarded as cute (such as kitten and puppy), lower scores for words referring to things of mediocre cuteness (e.g. mole and badger) and highly negative scores for words that convey the highest level of anti-cuteness (e.g. rat and zombie). There are plenty of things, however, for which talking about its cuteness does not really make any sense. For such words – including e.g. wind, temperature, airplane, cement, red, watching and so on – we would perhaps like to see zeros in our representation, something that we do not typically encounter in case of traditional distributed word representations.

The basic idea behind the sparse word representations used in the paper is that we wish to express pre-trained dense word vectors as a sparse linear combination of basis vectors such that the overall reconstruction error is minimized. The sparse coefficients can then be used as sparse word representations. Nevertheless such sparse word representations inherently do not try to take a stand on every aspect of every word, it does not necessarily follow that such representations line well with commonsense concepts. In order to get some insights, I release some of my findings related to this question.

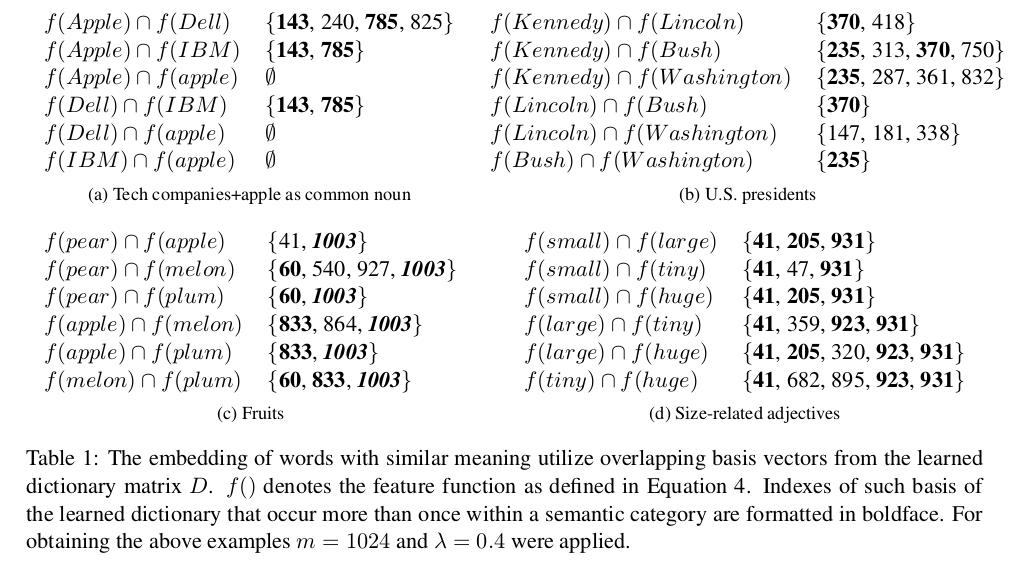

An earlier version of the paper presented at ACL included the below figure (which was later removed due to space limitations):

The above table illustrates that semantically coherent words indeed seem to rely on overlapping sets of basis vectors upon the reconstruction of their dense representations. While the previous table can be somewhat convincing, I conducted a less ad-hoc experiment as well based on relations in ConceptNet.

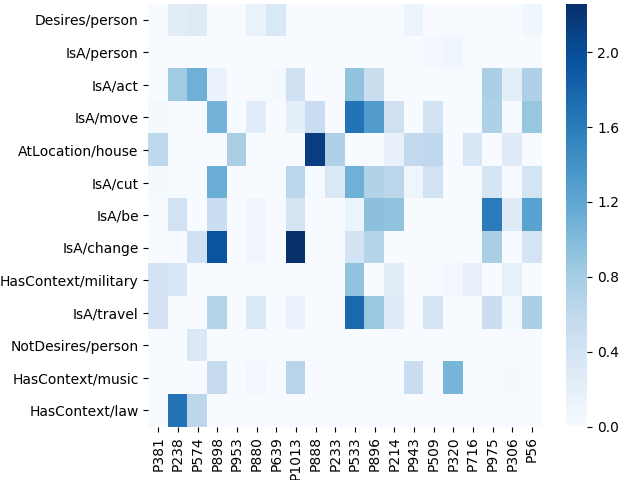

For this experiment, I took the sparse word representations and made a ConceptNet API call for each word to see what relations a certain word is involved. ConceptNet relations come in the form of e.g. ('/c/en/poodle', '/c/en/dog', 'IsA') representing an Is-A relation between poodle and dog. From these relations I built a co-occurrence matrix between the basis vectors and the ConceptNet relations. The co-occurrence statistics between the basis vectors and the ConceptNet relations were then used to quantify the association strength between the two by calculating positive pointwise mutual information scores.

It is illustrative to inspect which words lie the closest to the first few basis vectors and which ConceptNet relations are associated to them with the highest PPMI score:

| Basis | Top-1 | Top-2 | Top-3 | Top-4 | Top-5 | Most associated ConcepNet relation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P381 | village | neighbourhood | neighborhood | fort | township | AtLocation/house |

| P238 | amendment | decision | inquiry | obligation | petition | HasContext/law |

| P574 | stability | coherence | sensitivity | separation | efficiency | IsA/act |

| P898 | harden | darken | pierce | flatten | loosen | IsA/change |

| P953 | coal | oil | food | cotton | grain | AtLocation/house |

The above results seem to give a firm support that the representations obtained by employing sparse coding on distributed word representations can align well with human concepts. At the same time further experiments are definitely worth to be gone for in order to gain a better understanding of what parts of commonsense knowledge are/can be encoded in sparse word representations.